There is an urgent need to reduce the local and global environmental effects of transport (air pollution, noise, Co2 emissions). This requires among other things, reducing the number of motorised vehicles on the road. Many policies have been applied in several cities to persuade citizens to switch from private cars to public transport, walking, or cycling.

Yet, in almost all cities around the world, roads are still full of motorised vehicles. Road traffic levels have not declined much (or not at all). This is because of the increase in urban freight traffic. Demand for home deliveries had been increasing a lot before Covid. It has increased even more since then.

The solution is either making fewer deliveries or making more environmentally sustainable deliveries -for example, using “urban microhubs”.

Microhubs are small facilities where freight is received in bulk and is then re-distributed to nearby residential or commercial premises by low-emission vehicles (for example, cargo cycles). Microhubs can be in industrial or commercial units. However, because they do not require much space, they can also be in garages, car parks, or in underused spaces, such as under railway arches.

I have co-authored a study just published by the UCL Centre for Transport Studies, based on the results of a consultancy project for British Land (one of the largest real estate companies in the UK). In the report we discuss the benefits and costs of urban microhubs and how they depend on the location of the hub within the city. Download the report from here.

By shifting traffic from motorised vehicles (trucks or vans) to cargo cycles, microhubs benefit local communities, as they help reducing pollution. They also ease the pressure on roadspace, both for movement and parking.

Microhubs can also benefit shippers, freight operators, and customers. They allow for faster, more reliable, and more flexible deliveries, compared with conventional delivery. This is because freight is consolidated in the microhub, and consolidation tends to be an efficient way of organizing freight distribution. Furthermore, in congested cities, cargo cycles are often faster than bigger vehicles, like vans, because they can use streets closed to these vehicles.

But these benefits of microhubs are not certain. They depend on their location within the city.

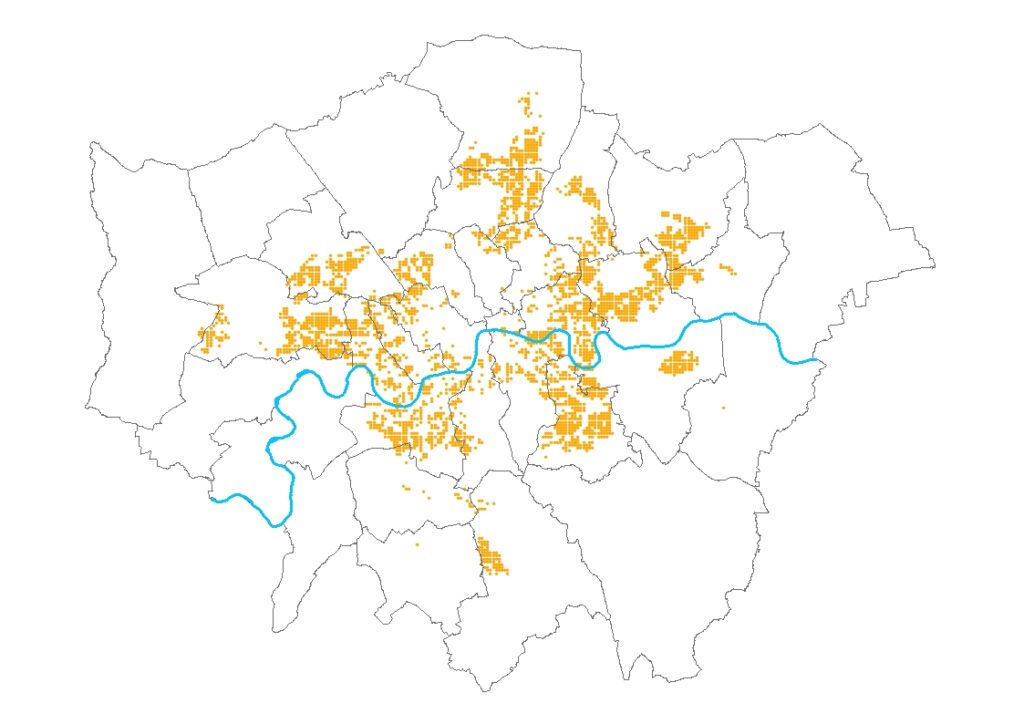

In the report, we used spatial analysis to identify the areas in London that fulfil essential conditions for the viability of the microhub:

- A minimum level of demand for deliveries in the surrounding area (from residents, business, or organizations).

- Suitable conditions for using cargo bikes, including the existence of cycle lanes/tracks in the vicinity, traffic calming measures, and general cycling safety (assessed based on the history of car-cycle collisions).

- Location near main freight distribution routes (as goods and parcels need to be delivered from bigger hubs to the microhub).

- Availability of a suitable pool of labour that can access the microhub either by walking/cycling or by frequent public transport.

The areas of London that fulfil these conditions are below. They are not very central areas. But they are not very suburban areas either.

The funder of the report (British Land) used its results to make their decision about where to invest in land for a microhub in London. That’s great for them but also for us. Research impact.

The area chosen by British Land is in Paddington, an area at the edge of central London, with good accessibility by road to outside the centre but at the same time good accessibility by cycle to inside the centre. This microhub can remove around 100 vans from central London, reducing environmental problems.

The report got attention from the general media. It was reported by the Evening Standard, a London newspaper. It was also reported by Zag Daily, a site specializing on innovations about cycling and micromobility.

A sister report, also commissioned by British Land, was published by Centre for London, reporting the results of interviews abour microhubs with freight and logistics experts in the private and public sectors.

Other microhubs exist in London. Of course, a certain company named after a South American river already has one. Other companies also have their own microhub, or share microhubs. In other cities, microhubs are starting to appear. So expect to see more cargo cycles around.