Question: What do people care about when they travel?

When people make decisions about travel (for example, where to go, how, and when), they consider various factors (cost, time, comfort, convenience, etc). Different people have different preferences about these factors. For example, some people prefer to get somewhere fast, even if that means a bit less confort. Others prefer to travel comfortably, even if that means taking a bit more time.

One way to know what people prefer is to use stated preference surveys. This means asking people what they would do, if they had a few options. The options differ in several aspects. Each survey participant answers several questions. In each question, the differences between options change slightly.

If many people answer the survey, we can calculate how people balance each aspect, on average. If one aspect is money, we can also calculate how people balance money with the other aspects. This is an indicator of the economic value of those aspects.

A variant of this is to look at people’s actual behaviour (instead of asking them about hypothetical options). This involves determining what options people had and which one they eventually chose. This method is called revealed preferences.

Example 1. Pedestrians

I was involved in several stated preference studies looking at how pedestrians decide were to cross a road, and how much they value not crossing the road. The results are reported here, here, and here.

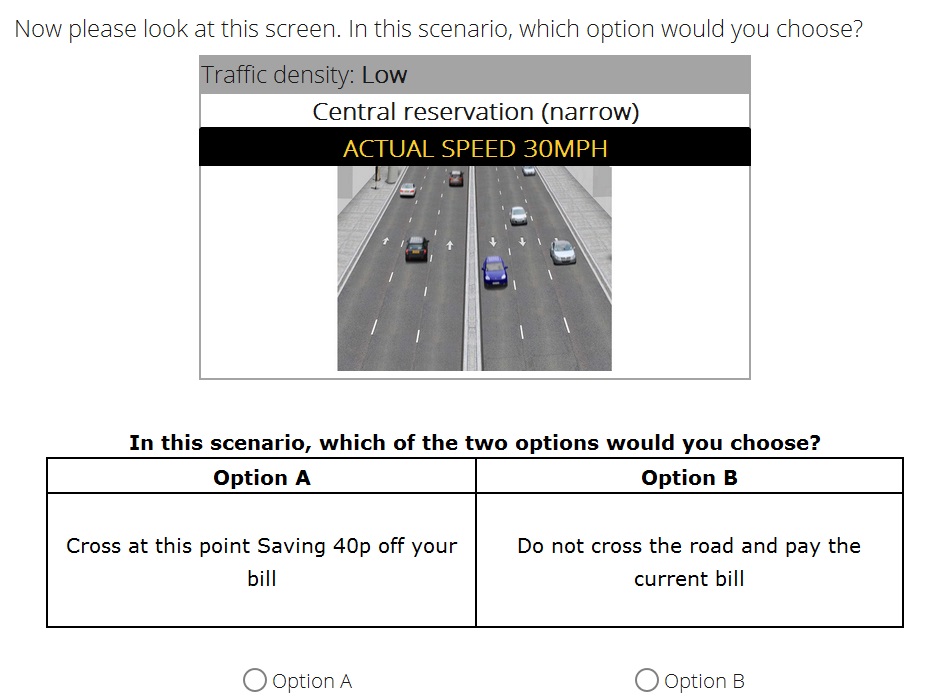

See an example in the figure below. The survey participants are asked to imagine that they are pedestrians who have two options A or B. In Option A, pedestrians cross a busy road (in a place without crossing facilities) and by doing so they can go to a shop on the other side where they can save £0.40 in their usual shopping basket. In Option B, they do not cross, and go to a shop on their side of the road, making no saving. The participants answer 8 questions like this, each one with a different type of road and a different amount for the saving.

If we consider all the choices made by all participants, we can calculate the value that people attach to, for example, not crossing a road with 6 lanes, compared with a road with just 2 lanes.

Example 2. Train users

I was involved in several consultancy projects for the rail industry in the UK, including studies to forecast the effect of railcards (e.g. for younger people, for war veterans), and to calculate the effect of changes to train services on rail demand.

The objective of one of these studies was to forecast the effect of changes to the rail fare structure. The fare structure in the UK is complex: there are many different types of tickets for the same trip. We wanted to know the effects of simplifying this. This is described in this paper.

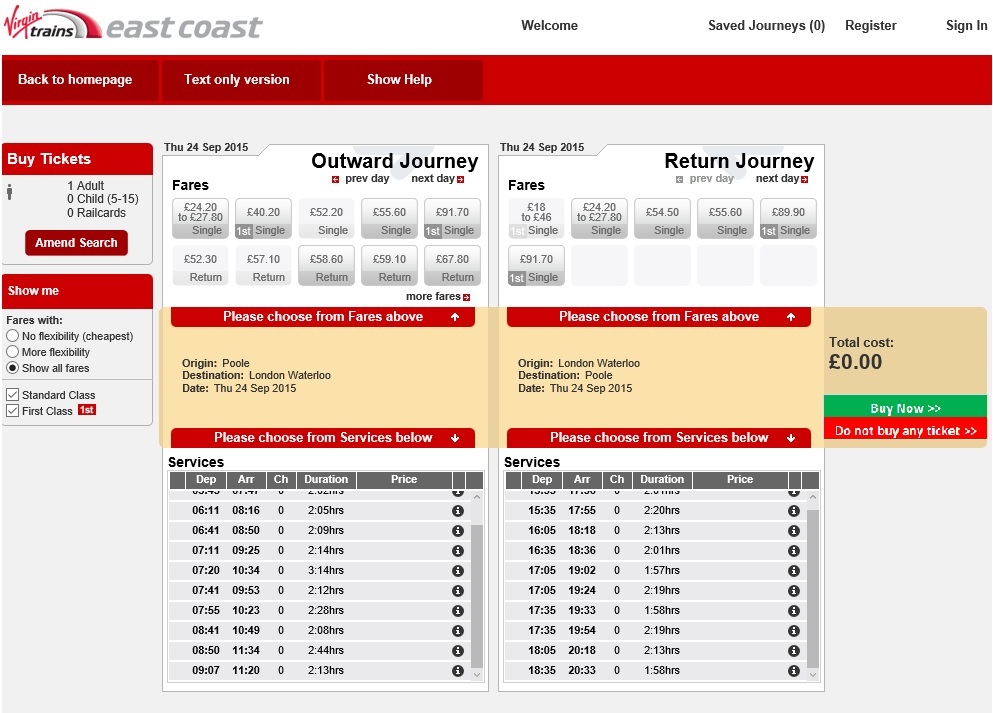

The choices were presented in a mock online rail booking webpage, as below. The survey participants searched when and where they wanted to travel. They then chose the ticket type and the train service they would use. If they chose a restricted ticket (for example, an off-peak ticket), travelling at some times (in this case, off-peak times) would not be possible. In some cases, the choices were complex (many options). In other cases, the choices were simpler. Like this, we can calculate how, on average, people balance travel time, cost, departure time, and the overall level of complexity of the choice.

We found that people liked complexity, because this gives them more options to choose from, and increases the chance of finding the option that works best for them.

Recently, I worked in another consultancy project using data from real users of an online train booking webpage.

Example 3. Road drivers

Stated preference surveys can also be used to study the preferences of road drivers. For example, I worked in a consultancy project calculating how people welcomed the possibility of travelling faster, but paying for it, in new motorways in Saudi Arabia. By knowing how drivers balance the two aspects (travel time and tolls), we can calculate the value of travel time savings.

In other projects, we analysed how people balanced the possibility of using express lanes, but paying for it, in motorways in Washington DC and in Brisbane, Australia. Again, we could calculate the value of travel time savings.

Knowing the value of travel time savings is not just a good-to-know thing. It is useful for the roads operators to fix how much the toll should be (or if it’s worth to have a tolled road at all).