Question: What happens to pedestrians when car use grows?

As cities become richer, their transport system changes. But, as we show in this paper, they can change in different ways, some more sustainable than others. The less sustainable ones are those where most people use private cars, rather than public transport, walking, or cycling. They are not sustainable because private cars contribute more to local and global pollution, per person transported, than those other modes.

The problem is that when people own more cars, and travel more with them, walking tends to become more difficult. This is because it’s riskier and less pleasant to cross the road when there are more cars on it. Furthermore, increased car use often convinces governments to give more roadspace to cars, or even to exclude pedestrians from roads. In this book chapter, we show how this is happening across most of urban Africa right now.

I am interested in creating maps of walking potential and walking conditions in cities where car use in increasing. Here are two examples.

Example 1. Praia, Cabo Verde

Cabo Verde is a small island country in West Africa. I have published this paper and this one about the effects of growing car use on pedestrians in the capital city (Praia). See also a post in the Africa page of the Walk Around the World section in this wbsite.

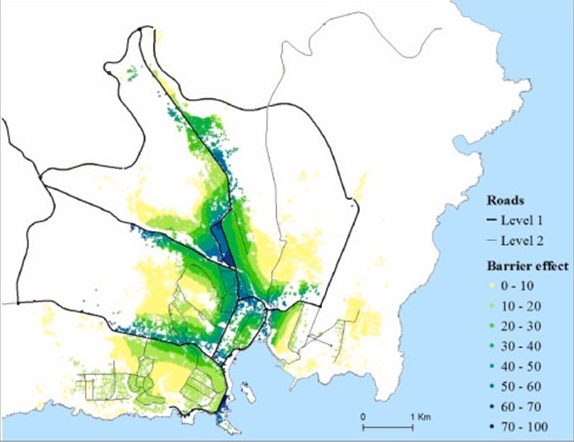

The papers include maps of walking conditions, and of how these conditions are affected by busy roads. As an example, the map below shows the barriers to walking caused by roads in Praia, in a scale from 0 to 100. In this scale, 0 is when people do not have to cross any major road to go to any nearby place. 100 is when they have to cross a major road to go to any of the nearby places.

In many cases, the indicator is above 70%. This is for example the case of an area in the geographic centre of the city, sandwiched between two major roads.

This type of maps is useful for governments to know where the main problems are and to antecipate the possible effect of building more roads or widening existing ones.

Example 2. Havana, Cuba

Havana is a city where walking is still the predominant method. But that is under threat because of increased use of motorised vehicles (cars and buses).

I worked in a project involving several UCL departments, the Universidad Tecnológica de la Habana, and the Havana local transport authority. We worked with local populations to map pedestrian conditions and to reclassify the road network, and identify factors that make streets more walkable. We produced policy briefs, which you can download from here.

The map below is an example. It shows the Havana road network. In this map, the roads are not classified in the usual way (primary, secondary, etc). That would consider only the importance of road for movement (of vehicles). Instead, in this map, the roads are classified in two dimensions: movement and “place”. Place accounts for all uses of roads that are not movement to go somewhere. For example, people waiting for buses, sitting, strolling, children playing, etc.

This type of maps is useful for governments because it shows that policies such as widening roads may benefit some users (i.e. those using the road for movement) but at the same time have costs for other users (those not using the road for movement). The map emphasizes that both types of users exist.